The Trench Watch's Place in WW1 | VARIO

The First World War was a massively important war in so many ways. The influences it has over us all are inescapable, though most people don’t really think too much about it. A small part of its influence is of course that most people have a grandparent or a great-grandparent who was involved in the war. But it's mostly that, over four years, the entire world was changed in nearly every way. Decisions made during and after the war affected (and still affect) the geopolitics of the whole world. Even the end of the First World War is cited as a direct cause of the Second - the one that most people are more liable to know about.

Of all the War’s myriad influences, the greatest is upon technology, due to the undeniable fact that the modern style of war, pioneered in this war, necessitates innovation and advancement.

This is relatively well-known, but when most people think of wartime tech, they think of planes, nuclear power, GPS or radio.

There is another thing today which followed the same path as all of those, but that most people don’t think of too much: the wristwatch. The origins of the wristwatch are actually a perfect microcosm of how the War affected technology.

Before the War, the wristwatch was barely accepted. Afterwards, it became a fundamental part of male fashion.

Now, to understand how the wristwatch became famous during the war, you have to understand exactly what made this war different. Why was the wristwatch made famous by this war in particular, and no other?

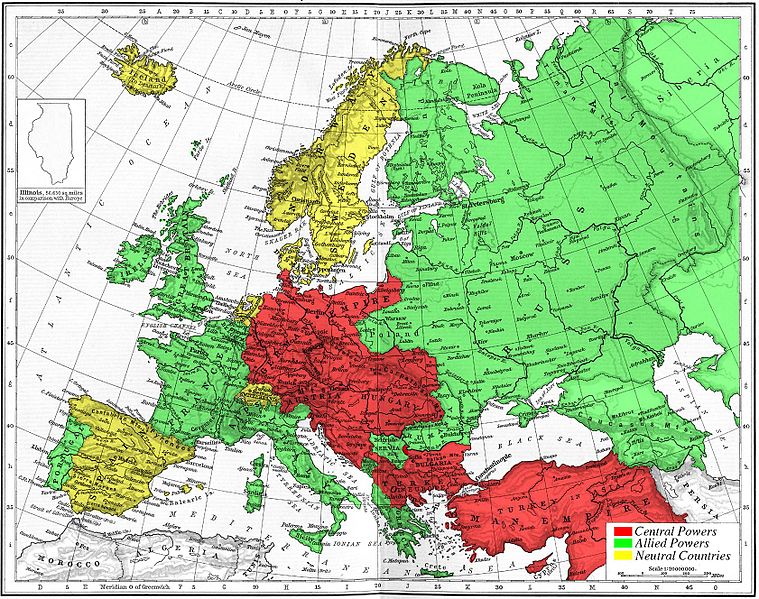

A map of Europe's alliances in 1915. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Explaining the story of the War can be a little difficult, since at its beginning all of Europe was tenuously connected by a lot of small treaties and alliances, but I’ll try to keep it short.

The two greatest alliances of pre-War Europe were the Triple Entente (Russia, France, and Britain), who became the Allies after they were reinforced by Japan, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Greece and the USA, and the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary and Germany; later joined by the Ottoman Empire).

Schools commonly teach that the start of the war was the assasination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary during a visit to Sarajevo on the 28th of June, 1914, but tension had been building up for a while: Germany had been preparing for war, in part by building a big, scary navy, Russia had been weakened by civil dissent, the Ottoman Empire had been failing to modernize smoothly and Austria-Hungary had been hungry for the Balkan states for years. Europe had been bracing itself for years.

After the assasination, Austria-Hungary decided to try and satisfy their hunger, feeling secure because of their powerful neighbor Germany. Following (unofficially) encouraged anti-Serb riots and a month of careful diplomacy, they sent a list of impossible demands to Serbia, expecting rejection. Serbia conceded to most of the demands, which the Austro-Hungarians declared as tantamount to complete rejection.

On the 28th of July, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Russia mobilized two days later. A day after that, Germany did the same, realizing that speed would be necessary ro defeat Russia and Russia's ally, France, who joined in to support Russia. England tried to maintain neutrality.

Unfortunately, the war with France stalled, so Germany invaded Belgium, meaning to bypass France's fortifications. Great Britain, allied with Belgium via an old agreement to ensure Belgian independence, was forced to declare war on Germany, finally deciding to help their friends in France as well. And if Britain was involved, then every British colony was too.

From there, the war continued on begrudgingly.

It eventually ended in 1918, the death toll reaching nearly 20 million – 10 million soldiers and 7.7 million civilians – as well as the injury of another 21.2 million soldiers. Today, WWI is remembered very clearly in most of Europe, especially in places where the poppies and stark white crosses mingle in vast fields.

Much of the First World War’s historical significance – aside from the unbelievably high butcher’s bill – is correctly attributed to the (obvious) fact that it was the first war to genuinely count the entire world as its participants. At first glance it may seem that it was a European war only, but with Europe’s colonial holdings in the fight, joined by most of South America following the USA, the War became entirely global.

And global war was a new thing. Completely new. There had been big wars in Europe before, no doubt, but one of those hadn’t been seen since the time of Napoleon, a century before. But even the wars against Napoleon didn’t concern much of anybody outside of Europe and, for a little while, the USA.

However, as mentioned earlier, WWI is also notable for serving as the bridge between two eras of military history. It was not exactly the first modern war, nor the first industrial war – nearly every war in the last half of the nineteenth century had the power of vast industry – but it used contemporary industry to the fullest extent possible. With that industry, its participants threw everything at the enemy, killed in extraordinary numbers, and created conditions so unbearable that almost an entire generation was scarred by the memory.

WWI was the first to imbue war with the need for technological innovation. After WWI, one-upping each other became a fundamental part of any war. It still is today.

Let me expand on this:

None of the innovations which defined previous wars (namely, the telegraph) were actively designed during those wars, by military-funded designers, for the exclusive purpose of gaining an advantage. If the tech was deemed useful, then the military adopted it, sure – but the work was done privately.

Therefore, nearly all of war before the Great War was the work of the strategists and the generals only, under whom the essence of war was the individual maneuvers – feints, dodges, retreats, rushes, false retreats. All required skill and artistry to implement while under fire. Of course, not every single exchange was a masterfully played game of chess, but strategy was still what every battle was made of. It was the deciding factor. Innovative skill was focused on the invention of new strategies and techniques.

This is not to say that the Great War had no strategy. It is just that the business of war became too big to micromanage. Strategy confined itself to the bigger picture, while new tech took over as the battle-winner. (The Schlieffen Plan – the German strategy for winning a war on two fronts – is an example of the grand strategy needed)

Troop numbers grew to such a huge amount that no battle could be won decisively by individual maneuvers, as the front lines were too wide and too easily repopulated with fresh soldiers. The meaning of the word "battle" actually seemed to lose its old meaning, considering that battles went on for months despite unbelievably heavy casualties. For instance, the longest battle of the War, the Battle of Verdun, lasted for 11 months straight.

The business of the war became what technology was used and how fast it could be produced. And when one side created a new technology, the answer was to invent your own, superior technology. When Germans used gas, the next step was to counteract the gas with a new invention – masks, while also making gas that could puncture masks, rather than creating strategies and techniques to identify and avoid gas attacks.

Planes also became popular, originally as a means to survey ground troops. However, by the war’s end, countries developed four classes of plane, each requiring distinct training and equipment: the scout, the artillery-spotter, the bomber, and the fighter.

Even during and immediately after the War, people realized the importance of all that new tech. In fact, A. Russell Bond, then-editor of the magazine Scientific American, wrote a book in 1919 – no more than a year after Armistice – about all the new things that were made during the War (it is available on Project Gutenberg: Inventions of the Great War).

British soldiers in the trenches at the Battle of Somme, 1916. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The part of WWI which created many new inventions, including the watch, was the trench warfare, which brought near-constant threats. Trench warfare is quintessential to every discussion of the War. It is a crystallization of everything that differentiated the War from all others.

Trench warfare began early in the War, during the German march towards Paris. Making easy way, they soon grew a bit too careless, falling into a retreat after the First Battle of Marne. However, the Germans' preparations taught them defense well, so they quickly and competently dug miles of trenches and settled down for a long, hard war.

As Bond put it, “The war of manœuver had given way to trench warfare, which lasted through long, tedious months nearly to the end of the great conflict.”

All of these trenches were created with basic similarities like zig-zagging and sleeping quarters, but the quality of the trenches was wildly inconsistent.

On the one hand, there were the Germans. Some of the German trenches in France are described by Bond as including “underground villages.” These could sometimes extend two stories below the ground, with rooms with board (or even papered) walls, complete with washstands, spring beds, kitchens, and full-sized mess halls. These “villages” were usually well-lit with electric lamps. Unfortunately, German trenches would degrade slightly in quality just a short while later in the war, as many of the soldiers stationed on the Western Front were pulled all the way to the East to fight Russia.

On the other hand, there were the Allied trenches, which started out as shallow, hastily made ditches. So shallow that no one could walk through them standing straight up, or they would be unceremoniously shot by snipers.

Realizing that their boys would have to live in these trenches, the Allies soon began to dig them deeper, so that the men could walk through them standing straight up with no concern for enemy snipers or machine guns. But soldiers living in them still had to deal with a lot of dangers, like gas or shell, and were tormented by lice and mud.

In all of the trenches there was that water and mud, which was often a danger in and of itself. In fact, standing in cold still-water for hours without moving, often with too-tight boots, the soldiers would develop "trench foot," a condition that could allow feet to become gangrenous.

Living amidst all of this mud and gas and shrapnel and frost meant that the soldiers desperately needed new inventions. Inventions describes a couple useful ones, including a very peculiar way of shooting called a”sniperscope," but neglects the trench watch entirely, maybe because the watch is admittedly not entirely an invention of the War. However, the improvement of the watch is innately connected with trench warfare.

1893 advertisement for the leather wristlet, meant for wear by bicyclists. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When they were invented, wristwatches were only developed for women. These watches were smaller and were attached to fine bracelets. Often, they were called “wristlets,” after the bracelet shape.

The majority of men disliked the wristlet. To them, there was an element of impracticality (not to mention implicit femininity) in the design: while a pocket watch was relatively protected from grime and mud and water in the soft embrace of a waistcoat or trouser pocket, even during heavy labor on the farm or the railroad, the wristwatch is exposed to everything that the wearer picks up, touches, gets near, submerges their hands in, or otherwise interacts with. This was less of a problem in a lady’s watch, since women – at least the women who could afford wristlets – were barred from the heaviest and dirtiest work, but to have a men’s watch solely meant to go on the wrist was frowned upon for the simple reason that it would get dirty.

The word “solely” is important there, since there was sort of a men’s wristwatch before the trench watch, in the form of a simple leather case and wrist-strap.

These leather cases (called “wristlets” as well) were no more than a leather strap with a large ring to insert a pocket watch into. One would take out their pocket watch, unbutton or unclasp the leather case, and slip the pocket watch into it, the crown poking out of the top for easy winding. These cases were still fairly niche – only accepted by the odd bicyclist, aviator, or, later, automotorist, but even these people took the trouble to remove the watch from the case once they reached their destination. To the masses, a watch on the wrist was grossly feminine, impractical and nothing more.

Of all those niches, the leather wristlet was the most important to the military, whose officers wore the case to save the time that would ordinarily mean fumbling to get the watch out of their pockets.

Military officers serving during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) were reportedly the first to realize en masse the practicality of having a watch that can be glanced at quickly and easily. Spending all day riding horses and fighting mobile guerrilla forces meant that digging in a pocket became too inconvenient.

In WWI, the need for a practical timepiece was amplified. With trenches, troops were spread out in a thin line across all of Europe. Timing was now more important than ever, with grand strategies like creeping artillery needing precise coordination to avoid embarrassing catastrophes.

And, because of the cramped, shared quarters of the trenches, uniforms were criss-crossed with a ridiculous number of straps meant to allow the soldier to hold everything at once. Canteens, spades, rifles, bullets, bandages, cigarettes, tin cups, extra shoelaces, grenades, gloves and socks were always on hand, so pulling aside the webbing and digging in a series of buttoned, overstuffed pockets for a watch took several seconds longer than it had on horseback in 1901. When timing operations to the second and facing an endless stream of machine gun fire, wasting those precious seconds trying to tell the time could be fatal.

But couldn’t they have used the same leather wristlets in WW1?

Well, no. Let me explain:

Besides the need for timing and the fatal inconvenience of digging in bottomless pockets, the soldiers in the trenches needed a few more things than the wristlets could provide.

The most notable problem would be the moisture: remember, these extensive networks of deep ditches were often muddy or partly flooded, so any watch would have to be proofed against the water, dirt and dust which the War was happy to provide. The Second Boer War, being in a drier place, didn’t require this from the wristlet.

Another thing was comfort. The watches inside leather wristlets were still pocket watches after all, if slightly smaller, but the short duration of their use usually offset the uncomfortable feel of it. They were much too bulky to be worn for months at a time without breaks as the trench watches were.

Also, because of their bigger size, leather wristlets were more liable to bang against the side of a trench or catch shrapnel. The glass in pocket watches was fragile, too, so accidentally banging your wrist against a piece of dirty wood while mindlessly scrambling to take cover from a shell could shatter the crystal, rendering the watch useless and even mildly dangerous.

There was also the issue of legibility. Pocket watches, and thus leather wristlets as well, normally used Roman numerals, which looked fancier and worked well with Europe’s post-Renaissance affection for all things classical. But during battle, converting “VII” into “7,” then that into “35” in one’s head could take a second too long.

The final thing was simply the economy of it. When leather wristlets were in production, they were only meant to be used temporarily, to delay the issue until it was an issue no longer. If someone was about to be in polite company, the normal thing to do was to replace the watch inside one’s waistcoat and continue on as if the concept of a wristlet was completely unknown to them. Society refused to accept a regular wrist-only watch because, with the leather wristlet, society could have a watch both ways: formal and informal, decorative and pragmatic, pocket and wrist. But during the War, there was no polite society to look forward to between shell craters, so producing two lines of product – one a pocket watch that couldn’t be worn in the pocket and the other a leather strap that was impractical to remove and uncomfortable to wear – was just a bad investment.

The answer was clearly to just have a regular, simple wristwatch. Enter the trench watch.

Trench watch manufactured by Patria before the Great War. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The term “trench watch” does not refer to a watch designed specifically for the trenches; instead, it refers to the style of watch which became famous in the trenches. Actually, trench watches had been around for a little while before, but the market was still basically dominated by those leather wristlets.

Because the difference between wristlet and wristwatch is relatively little, many people all had the same idea at once, seen through the practice of soldering wires onto regular pocket watches. Thus, no one could claim to have invented the wristwatch. By the time of the War, a plethora of companies had reached the same general trench watch design: Lancet, Rolex, Elgin, Patria, Waltham, Electa, and Hamilton, to name a few. But those companies who made them did not make large runs until the War.

When the War actually came, the wristwatch solved several of the wristlet’s problems in one move:

In the first place, trench watches, like the leather wristlets, were easily accessible. However, unlike the wristlet, the trench watch was smaller and more comfortable, so it was unlikely to get caught on a sleeve and soldiers could wear it for months with minimal complaints.

Secondly, instead of Roman numerals, trench watches used bigger, Arabic numbers. No time was wasted when glancing at it. Later, officer’s guidelines strongly suggested that British officers be equipped specifically with lumed watches, allowing the time to be read at night by virtue of radioactive radium. Even better.

Thirdly, trench watches were advertised as having “unbreakable glass,” which could take a few knocks without shattering. And what’s more, most brands also stocked shrapnel protectors – a sort of circular grill to fit over the watch face and prevent anything from directly hitting the crystal.

Fourthly, trench watches were simple to produce. In fact, since smaller ladies’ watches were already being produced, it was really easy for factories to switch to making slightly bigger parts for men's watches. And though there was the perception before the War that wristwatches, being meant more for decoration than for work, were less accurate, this was untrue by the time the War started. Rolex in particular received a Class A precision certification from the Kew Observatory in Greenwich on July 15th, 1914, just 13 days prior to the War’s beginning. It was the first wristwatch to do so.

Finally, waterproof trench watches circulated later in the war, finally solving the moisture problem. The Waltham Field & Marine was the first of these. With the countless square meters of mud and wet clay present in the trenches, these waterproof (and “dustproof”) watches were extremely helpful to anyone who was prone to falling down or who was required to dig and crawl.

While the War lasted, the pros of the wristwatch were obvious, but the War had to end eventually.

A vintage remembrance poppy from Canada; date unknown. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The War ended in 1918, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. It killed millions of people and completely upended the entire Earth’s power structure in just 4 years. It was the biggest war the world had ever seen.

The end of it was obviously a momentous occasion.

The civilians – at least those in the winning countries – felt elated. They had managed to survive one of the most trying times in human history.

The survivors returned home, most of them mentally or physically scarred – all of them the bravest lads the world knew of, and they were wearing wristwatches. They refused to take them off! These people were the pinnacle of bravery and then they came back with something innately feminine on their wrists?

Needless to say, this created a lot of confusion. One of the two ideas had to change: either the soldiers were feminine or the watches were masculine.

Wristwatches suddenly became masculine.

Because of the watches' new image, more and more men started to wear wristwatches, despite the fact that there was really no change in their practical value among civilians. Nevertheless, they continued to grow in popularity until they soon outnumbered pocket watches by fifty to one.

And by the time of the next big war, wristwatches dominated pocket watches in nearly every way. They were solidly established in the wardrobes of everyone from the soldier to the industrial wage-laborer to the rich politician.

During the Second World War, watches played an even bigger role, expanding in their uses and designs.

Afterwards, wristwatches for every lifestyle were created, as the industry expanded into every corner of society. If you were a diver, doctor, or builder, then they had a watch for you. By the end of the twentieth century, wristwatches had conquered the world, but at the beginning of it, they were ridiculed by most.

Of course, today, smartphones and smartwatches have supplanted classic wristwatches as the default timepieces of the world. But, it’s worth remembering the history that brought the watch in the first place, in the same way that it's worth remembering the history of airplanes and TVs and trains, because watches have affected the world too, albeit less directly.

It’s really quite inspiring how a simple technology like the wristwatch went from nothing to everything in less than a century. Plus, when you dig into the history of specific watches, you find a lot of interesting tidbits.

Sources, in alphabetical order:

- A Brief History of the Wristwatch https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/05/history-wristwatch-apple-watch/391424/

- AMSCO - World History: Modern; https://archive.org/details/amsco-wh-modern/STUDENT%20AMSCO%20PDF/20%20CH%207/

- Great War Trench Watches; https://www.vintagewatchstraps.com/trenchwatches.php

- The Illinois Watch: The Life and Times of a Great Watch Company

- Inventions of the Great War; https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/45269

- The New Cambridge Modern History – Volume XII; https://archive.org/details/iB_CMH/12/mode/1up?view=theater

- The Outline of History

- The Oxford Companion to Military History

- Storm of Steel

- Trench Foot; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482364/

- Wristlets; http://people.timezone.com/mfriedberg/articles/Wristlets.html

- WWI Vets Popularized the Most Important Accessory in A Gentleman’s Wardrobe https://www.businessinsider.com/watches-after-wwi-the-male-accessory-2016-5

About the Author:

Milo Perzo is a young essayist and author from Southwest Louisiana. He is currently studying history and linguistics, and has been involved in many community projects in Lake Charles, where he lives. He spends his time writing, studying, or trying to cook.

A remake of the classic Trench watch by Vario

A remake of the classic Trench watch by Vario

For the full collection of 1918 WW1 Trench watch, please visit

https://vario.sg/collections/1918-trench-medic

How the Trench Watch Became the Modern Wristwatch We Know Today

https://vario.sg/pages/how-the-trench-watch-became-the-modern-wristwatch-we-know-today-vario

A Man and his Trench watch

https://vario.sg/pages/a-man-and-his-trench-watch

Story of 1918 WW1 Trench watch

https://vario.sg/pages/ww1-trench-watch

Buying A Microbrand Watch? Here's Everything You Should Know

https://vario.sg/blogs/products/buying-a-microbrand-watch-heres-everything-you-should-know-vario

댓글 남기기

이 사이트는 hCaptcha에 의해 보호되며, hCaptcha의 개인 정보 보호 정책 과 서비스 약관 이 적용됩니다.